“Grasses are invasive here,” my Kānaka Maoli agroforestry collaborator told me earlier this year. The statement seemed odd to me then, as I thought about the numerous homes with “nice” lawns, the many picturesque ranches across the islands dominated by different grasses, and the resorts and estates considered by many to be “luxurious” in part due to their expansive fields of neatly manicured grass.

The term “invasive” is political and contentious—depending on one’s goals, intentions, and point of view.

But I began to understand what my collaborator meant by his statement when he took us up Kohala Mountain to see how the many native trees, ferns, and other plants we’d been working with behaved and thrived together in mature communities.

With permitted access into Parker Ranch—one of the largest cattle ranches in all of the “United States” and the fourth or fifth largest landowner in Hawaiʻi, holding over 100,000 acres—we drove through its seemingly endless rolling hills of pasture, eventually meeting its fenceline that bordered a protected forest reserve. The contrast on either side of that fence was stark. On the side that we came from stood an un-arbored landscape blanketed by vast fields of grass, sparsely speckled with the remnants of long-decayed trees. The side that we climbed into was a densely canopied wet forest. Even from afar, one can see this distinct boundary—a broad, solid band of light green makes up the base of the mountain with a sudden transition into dark green beyond the linear and angled perimeters of the cattle fencing.

As we bushwhacked our way in deeper, I felt like we were entering an entirely different world.

In contrast to the heat from the open pastures behind us exposed to direct sun, it was cool under the tall canopy of the dominant ʻŌhiʻa lehua trees—which make up 80% of Hawaiʻi’s native forests. They are known to be vital to watersheds across the islands: “ʻŌhiʻa grows naturally with all kinds of mosses, ferns, and keiki (young) plants all over its branches. They are like a big fishnet, capturing tiny mist droplets that slowly seep down into our aquifers,” writes Heidi Bornhorst.

Blair Langston of Pilina ʻĀina shares that “Ohi” in Hawaiian means “to collect”—with ʻŌhiʻa in part named so to refer to their role as water collectors. These trees have certain morphological characteristics that make them up to 50% more effective at drawing in water when compared to other non-Hawaiian tree species. Langston also emphasizes the saying, “Hahai no ka ua i ka ulu lāʻau,” which translates to “The rain follows after the forest.”

“Development”—of relationships

In front of me, I felt the conversations I’d shared with various people on Green Dreamer (including Christine Winter, Andreas Weber, and Eben Kirksey) about the illusion of a neatly bounded individual self come to life. Indeed, there was no clear concept of separation—with plants growing on top of each other, the roots of one joined with those of another, the seemingly boundless moss Sphagnum palustre who has cloned themselves for 50,000 years carpeting the floor and stretching upwards, becoming the skin of trees and a moist growing medium for new seedlings.

While the forest was lush, however, I remember mentioning that it felt very “clean”—though that wasn’t the right descriptor for what I meant. I later realized this was precisely because of the absence of two-plus feet tall grasses that would have made it difficult to see the ground. Instead, the forest floor consisted of flattened layers of leaf litter and shallow mats of mosses. As Rhett A. Butler writes: “The forest floor of primary tropical rainforest is rarely the thick, tangled jungle of movies and adventure stories… Instead of choking vegetation, a visitor will find large tree trunks, interspersed hanging vines and lianas, and countless seedlings and saplings and a relatively small number of ground plants.”

The whole intergenerational community showcased time as continually folding back into itself. Younger trees grew right at the base of their senior relatives as if encouraged to focus their early years on rooting themselves downwards to establish their networks of relationships. All the while, the filtered canopy from the elders humbled their upward growth. This is what German foresters such as Peter Wohlleben of The Hidden Life of Trees call “education by shade”: speaking to how slow growth under the canopy of Mother Trees promotes stronger foundations and resilience against sickness and environmental threats.

While there are some pioneering or non-forest trees that thrive in solitude, I think about Wohlleben naming the uniformly grown trees that line streets as “street children”—left to navigate the world on their own without guidance from wiser generations nor relational support from access into well-established mycelial networks underground.

Walking deeper into the forest made me question dominant landscaping aesthetics and formulaic protocols of planting small trees ten feet apart and larger trees thirty to fifty feet apart. I assume these suggestions are based on how wide and tall the trees potentially might grow—what is visible to the human eye. But what about the complex relationships immeasurable by our tools that different generations of plants, fungi, mosses, and microorganisms can benefit from having opportunities to develop?

Along the veins of my piece “Reorienting Growth,” I would be curious to reorient the dominant interpretation of “development” being “the process of converting land to a new purpose by constructing buildings or making use of its resources,” according to Oxford Languages.

What if we focused “development” on enhancing and advancing the land’s own place-based intimacies?

The relational lens of climate change

I write to you now as I recover from writer’s block and “burnout.” Though in this moment, that saying feels inappropriate. Thankfully, my friends who live in Maui are safe from its recent fires. But I still feel the weight of the tragedy as I learn of the too many human and more-than-human lives taken, the hundreds of people who have yet to be found, and the relatives of my friends who have lost their houses.

As I watch the news unravel, I encounter more and more reporting attempting to position this wildfire as the result of climate change. While it isn’t unrelated, in reality, it’s hard to attribute any singular event to the climate crisis.

What I think is worthy of underscoring is how narratives that blame climate change for certain disasters in order to prove a point tend to overgeneralize the story and oversimplify the solutions.

While imbalanced global greenhouse gas emissions are definitely key aspects of the larger picture, they are overly broad strokes when left to their own, as they limitingly justify top-down techno-solutionism and lead people to gloss over local contexts that also have many lessons to impart.

As Professor Kapuaʻala Sproat shares:

“Part of the reason for this extraordinary tragedy in West Maui is that there has been more than a century of plantation water mismanagement in this area. It's because of extractive water policies, where water hasn’t remained on the land and invasive grasses have come up. That's what created the tinderbox and this unfortunate situation of the tragic fire that took place earlier this month.”

It is possible that the broader climate change contributed to the island’s recent drought conditions. But crucially, historic changes in power dynamics, local water management, and land stewardship changed the microclimate, water cycle, and biocultural community of the region—fueling the grass-fire cycle, “where abundant fine fuels from invasive grasses lead to more frequent burns, after which the same grasses are able to outcompete native plants, grow back quickly, and perpetuate the cycle,” according to the North Central Climate Adaptaion Science Center.

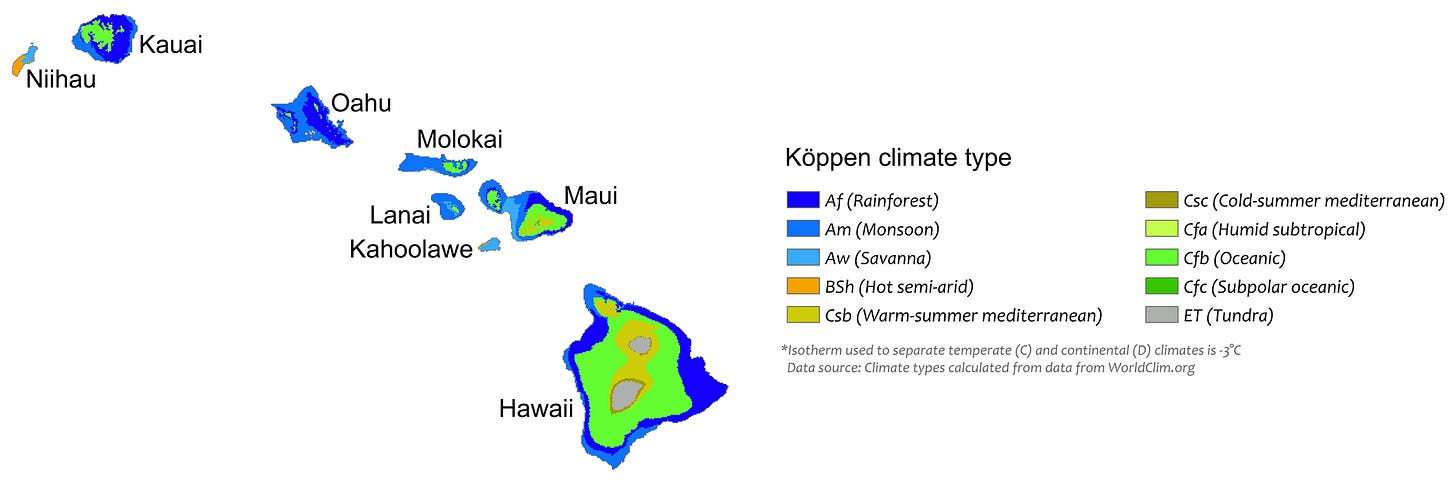

Change isn’t inherently bad—how drastic and sudden are the changes, and what are their cumulative consequences? Grasses and fires are also not inherently destructive—their impacts are highly contextual. The Hawaiian islands embody diverse terrains that range from humid tropical, arid and semi-arid, temperate, ice or alpine, and more. Leeward sides of larger mountains tend to receive much less precipitation, some areas of which are dominated by native dry grasslands of pili grass historically maintained through regular burns.

The deeper takeaways, for me, emphasize the non-binary differences between the trends of changing with and changing against—co-evolving with in ways that enrich the complexities of a place or changing disruptively in ways that unravel established webs of life.

Thinking about traits as interactive

Farmers and land stewards down the Hāmākua Coast and beyond have been battling the aggressive spread of trees like waiawi (strawberry guava); fast-growing eucalyptuses often considered safety hazards; and grasses like guinea grass and molasses grass introduced in the late 18th century by European ranchers wanting to bring in drought-resistant livestock feed. On either side of the main highway, there are now immense eucalyptus stands dominated by guinea grass as their understory—the result of misguided “reforestation” plans after the sugarcane plantation era.

The implications of these historic, large-scale land-use changes are immense, however. Because the traits of plants (and other beings) are not merely descriptive; they are also interactive and intra-active.

If introduced grasses come from savannahs that are very dry and renewed through fire, they are not just “drought-tolerant.” When seeded and spread across otherwise wet regions, past a certain point of prevalence, they can start to alter existing local water patterns to their preference. If eucalyptus forests consider fires essential for their regeneration, they are not just drought- and fire-adapted. They can also start to create or amplify conditions that lead to more fires.

“Eucalypts typically let through a lot of light, allowing other vegetation types such as scrub and grass to grow beneath them. But they won’t regenerate… if what is growing beneath them over the years becomes too dense. Most eucalypt species, therefore have evolved traits that allow them to survive and prosper in the fires that will clear that undergrowth. […] ‘A large proportion of Tasmania’s flora fits into this fire ecology. Pea plants, wattles—their germination is stimulated by heat and smoke. Fire is really, really important in Tasmania.’

At the centre of it all, though, is the eucalypt… ‘They withstand fire, they need fire; to some extent, they create fire,’ Bowman says. ‘They’re highly, highly flammable. And on a hot day, you can smell their oils.’” –John Henley via Firestorm.

I cannot help but pause here to critique standardized environmental impact assessments that consider certain trees or crops as more “eco-friendly” just because they require less water to grow. Industry people in the “sustainable fashion” space, for example, often tout, “This fabric is made from the wood pulp fibers of Eucalyptus trees which are fast-growing and require less water, and therefore it is more sustainable.”

If the goal were to harvest as much wood as “efficiently” as possible, that might be a reasonable conclusion. But it is overly reductive. What about all other forms of impact? In Brazil’s Bahia state, the Pataxó people have been fighting to reclaim their lands against such plantations that feed multinational pulp production—noting their serious damage to the entire region and their ways of life.

This leads me to wonder about the different directions people orient “sustainability”—to sustain economic growth, to sustain biocultural communities of life, or something else?

Presumed “advantages” of certain crops are meaningless without situated contexts as to how those traits interact with a specific region. Even with the best of intentions, those imposing universalized “solutions” without an in-depth understanding of place can contribute to their deterioration.

Reconfigurations remake the world

How a plant’s traits contribute to changes in their environments is relative to place. For example, ʻŌhiʻas have evolved to become extremely adaptive. Some of them are “the first plants to colonize fresh lava substrate, and are therefore instrumental in the process of soil development and ecological succession,” according to the University of Hawaiʻi. Even though these trees might be “drought-tolerant,” their pioneering presence in otherwise barren lava fields is what begins to generate soil and cycles of water capture.

There are nuances within the same species as well based on how they are “configured” in the body of their larger community. Wildland fire expert Pablo Akira Beimler of Hāmākua noted that fire risks in eucalyptus forests where the trees are spaced further apart are greater than those of crowded eucalyptus stands—in part because the latter fosters more shade, holds more moisture, and prevents as prolific of understory grasses. These context-based details are essential to consider.

Regardless, the underlying points remain. “Allelopathy” in the world of ecology refers to when certain trees or plants chemically alter their immediate environments in ways that make them harsher to certain species of competition and more hospitable to their own kind. Rather than just applying this term in a very individualistic way, though, I would offer that we can also understand this concept metaphorically at larger levels:

The presence of different species inevitably contributes to the remaking of place in their own ways—potentially affecting community dynamics and diversities in favor of their own thriving.

This is not to push for some purist stance in terms of who can or can’t plant what where, but it is a call to recognize the weight of what it means to make decisions for land mangement—given that every being has interactive impacts beyond their mere existence or function to serve some aesthetic, productive, or other purpose.

The most advanced water technology

Back in the cloud forests of Kohala Mountain, I thought of my friends, aunties, and uncles with land-related projects on the island who have expressed concerns over the decreasing levels of rain over the years and decades. According to Hawaiʻi’s Climate Change Portal: “Rainfall and streamflow have declined significantly over the past 30 years. 90% of the state is receiving less rainfall than it did a century ago, with a particularly dry period beginning in 2008 through the present.”

Climate narratives that center the water cycle—which regulates heat and helps stabilize climates—feel pertinent. But the story is not monodirectional in that climate change alters rain patterns. It is also that place-based biocultural changes transform hydrological cycles in ways that drive climate change.

“The way the global water cycle works is that water evaporates from the oceans, condenses into clouds that blow onto dry land, where it then rains down and trickles into streams and rivers that flow back into the ocean.

However, this straightforward explanation omits one crucial fact: without trees, every cloud would rain down within 600 kilometers of the coast, leaving the inner parts of continents bone dry. Trees essentially act as gigantic water pumps, transporting water further inland. When it rains in a forest near the coast, much of the rain remains on the leaves of trees and the forest floor. This water then evaporates, forming new clouds that make their way further inland, where they rain down.” —Insights from The Hidden Life of Trees.

Imagine big agriculture converting significant swaths of rainforests into monoculture plantations for palm oil, eucalyptus, pasture, or corn, hoping to take advantage of the region’s “naturally” high rainfall, and then blaming the larger story of climate change for increasing droughts without holding up a mirror to themselves.

How can a historically forested region bring in the same levels of moisture when large chunks of their organs—their highly advanced technologies of water capture, sequestration, and recycling—have been excised by the reductive logic of capital?

The even more concerning reality is that deforestation in one area can produce ripple effects in its impact far beyond those boundaries.

“ʻThe downwind effect of deforestation is not limited to the tropics. China receives a very large fraction of its rainfall from water that is recycled from evaporation on land,’ [Patrick Keys] told Yale Environment 360. It ‘has very high potential for changes to its precipitation driven by upwind land-use change’ as far away as Eastern Europe and the jungles of Southeast Asia. […]

In the Americas, he warned that the Brazilian megacities of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo and Argentina’s Buenos Aires could also be vulnerable because much of their rainfall originates in the Mato Grosso region, where forests and grassland are rapidly being replaced by corn and soy fields.

And what of Africa, the region of the world whose people are most dependent on rain-fed agriculture? […] Keys estimates that up to 40 percent of sub-Saharan rainfall is created by moisture that has been recycled by vegetation. In the arid Sahel region, the figure may rise to 90 percent...” –Fred Pearce via Yale Environment 360.

Recognizing the differing timescales of development and regeneration needed for wet forests compared to fire-adapted ecologies, I think about how much more difficult it is to reforest a region once its intergenerational and multilayered trees have been decimated. I also wonder about the feasibility of breaking grass-fire cycles once they have been set into motion. After all, the process of (re)establishing the stability, complexity, and diversity of forest communities takes decades, centuries, or longer.

“Rainforest will not readily return on lands with agricultural monocultures that have been devoid of forest for several years and have highly degraded soils. Tropical soils rapidly become inhospitable to growth due to swift leaching of nutrients caused by heavy rains and intense sunlight. […]

In the rainforest, most of the carbon and essential nutrients are locked up in the living vegetation, dead wood, and decaying leaves. […] Decaying matter (dead wood and leaf litter) is processed so efficiently because of the abundance of decomposers including bacteria, fungi, and termites. […]

The dry air of the forest clearing also desiccates the leaf litter, causing the mycorrhizae to die. The elimination of the symbiotic mycorrhizae reduces the capacity of trees to take up nutrients from the soil. This fungi is especially difficult to replace since each species of tree may have its own symbiotic species of mycorrhizae. Regeneration is further stunted by the rapid encroachment of tough grasses and shrubs after the clearing of forest.” –Rhett A. Butler via Mongabay.

Holding the messiness of everything

The recognition that there are “allelopathic” impacts of different forms of land management poses some big questions. These include how we systemically realign economic value with the non-quantifiable living and cultural currencies of place; how to hold accountability when it comes to the cumulative effects of land conversion shifting the microclimates of entire regions; and the ethics of private or national land interests being able to do whatever they want without consideration as to how that might affect communities beyond their territories.

There is some hope, as nations have already come together to work on agreements to govern waterways that cross international borders. But “the rivers of moisture in the atmosphere are rarely measured and never governed,” Pearce writes.

“A deal on sharing the water will be pointless if rains falter in the Ethiopian highlands because of deforestation in the distant Congo basin.”

On Hawaiʻi Island and beyond, many are in extremely tough positions today as they inherit troubling trends initiated decades or longer prior. But I do wonder: How can the necessary work of healing living communities outweigh the incentives of extractive land use? And with limited government grants and nonprofit funding, how can people be supported to help 1) contain aggressively spreading “weeds,” 2) take down hazardous trees that do not have cost-effective market value, and 3) plant slower-growing native species for biocultural revitalization—when there are simultaneous and urgent financial pressures for basic living?

None of these goals should be pitted against one another, which is why any dissonance feels deeply systemic.

Just like invitations from the field of Somatics to heal narratives of the mind/body/spirit split, a calling to heal the conceptual divides of nature/culture/economy seems to grow louder and clearer.

In spite of the many challenges present, people have been taking matters into their own hands. Hui Mālama i ke Ala ʻŪlili, an organization of Hāmākua Hikina, has been harnessing the power of community and following the principles of agroforestry as practiced by their Kūpuna (Elders and Ancestors). “It really begins with the transitioning of eucalyptus trees—felled and removed—beginning the process of mulching, fencing in the area we’re working in to keep wild pigs out, rebuilding soil, planting of all of the different native species,” says Noʻeau Peralto, Executive Director of the nonprofit. “Central to that agroforestry model we’re planning to restore in Koholālele is the ʻulu (breadfruit).”

There is no “pure” way forward; living communities are in constant transformation, and what is considered “healing” for an already remade place looks different than simply turning back the clocks to a “purer” time. In my conversation with Thom Van Dooren, he critiques projects attempting to resurrect long-lost species because the threats and changes that pushed them to extinction have likely only furthered. This means that outside of strictly controlled settings, current conditions are unlikely to be conducive to their survival and wellbeing. Van Dooren, therefore, questions the true intentions of such endeavors.

Decolonial perspectives on “invasive” species are also multilayered. For example, Dr. Catriona Sandilands pushes back against the pervasive use of herbicides* to get rid of them:

“Invasive plant eradication is a multibillion-dollar industry, the largest proportion of which goes into the pockets of companies like Bayer and Monsanto… Just getting rid of so-called invasive plants without thinking about the relationships that brought those plants to North America is like treating the symptom and not the cause of the problem. […]

The problem… is not so much any given invasive plant or the presence or absence of said plant; it's the invasive land ethic, which includes the widespread use of chemicals to eradicate invasive plants.”

While I resonate with such philosophical critiques, I caution against purist judgments that do not hold space for the messy, place-specific considerations of different practitioners. Several farmers and reforestation workers that I have worked with, for example, incorporate the bare minimum use of herbicides* needed to assist with containing guinea grass, cane grass, and waiawi—the swift spread of which can quickly become much more labor-intensive or nearly impossible to manage. Others might turn to mechanical solutions such as using heavy machinery or large plastic weed mats—all of which have other associated concerns of their own. In the context of a world that forces people to treat time as a limiting resource for competing interests, I feel for those having to weigh their limited decisions given their own field knowledge and unique circumstances.

Although Māori scholar Dr. Christine Winter understands her community’s responsibility to protect plants native to their ancestral lands, she shares, “[Invasive species] are there not because they have asked to be brought here. They are as much of a victim of colonization as Indigenous peoples around the world. How it's dealt with, I honestly have no resolution. I feel really torn about it.”

Regenerating my own cycle of creativity

I still have more questions than answers. Coupled with some personal crises, this prolonged sense of uncertainty has contributed to my writer’s block from imposter syndrome—questioning whether I can add anything meaningful amidst info-overload, questioning why my voice even mattered, and questioning whether my metrics of slow growth over the years mean that I need to pivot.

In a way, it feels like I have been battling a metaphorical grass-fire cycle of my own which has been drying out my creative juices—

where the ways I hope to show up cannot compete with more mainstream ways of operating, leading to slower growth, where comparison games perpetuate self-doubt, making me want to shrink, but where doing so further dampens my motivation to engage with the conflicting work of social media, marketing, and fundraising that are all necessary for sustaining and growing my counter-culture media platforms.

But then I think about the hundreds of midstory māmaki trees I helped to transplant this last year under ʻŌhiʻa and Koa canopies that were initially overtaken by guinea grass and waiawi. It has been extremely laborious to haul buckets to manually water and support these wet forest seedlings to take root—through a wet season which was not wet, then into the dry season. Nevertheless, it has been affirming to witness the turning points when they have tapped their roots deep enough into the ground and water table to be able to take off on their own. This teaches me that no matter how uneasy the earlier phases may be—especially against systemic barriers—my work, too, might one day find its place and turning point.

For now, I will take inspiration from the forest wisdom of slow growth and keep honoring and nurturing my own cycles and ebbs and flow of creativity. I will also remind myself that systemic and cultural transformations depend on deeper relational shifts and expansions in worldviews—even if they are more “underground” and less visible or measurable forms of impact. If this piece moved something for you, it will have made coming out of my content drought to write again well worth it for me. I send my warm regards and thank you for your continued presence and support.

[* Correction made 8/30/23 from “pesticides” to “herbicides.”]

I want to hear from you! Amidst my writer’s block and imposter syndrome, I would greatly appreciate receiving inspiration from my most engaged, supporting subscribers of this newsletter and/or Green Dreamer.

I’ve shared my struggles with broadcast media before in how it prevents intimate engagement and can feel overwhelming when trying to hone in on a sense of direction. What would really help to counteract that for me is to have more context as to who you are and where your curiosities have been leading you!

Please comment below or send me an email at greendreamerkamea@gmail.com to share a little about yourself—such as where you are from/based, what field of work you are involved in, what bigger challenges, issues, questions, or subjects you’d be keen on having me explore or attempt to answer, or past UPROOTED articles or Green Dreamer episodes you especially enjoyed. Thank you in advance for your affirmations and input on future topics that we can dive deeper into together!

Additional resources:

“Rivers in the Sky: How Deforestation Is Affecting Global Water Cycles” by Fred Pearce

“How Swaths of Invasive Grass Made Maui’s Fires So Devastating” by Shi En Kim

“The wisdom of Mother Trees and old-growth forests” with Suzanne Simard via Green Dreamer

“Clearing Forests May Transform Local—and Global—Climate” by Judith D. Schwartz

“Eucalyptus: California Icon, Fire Hazard and Invasive Species” by Liza Gross

Updates from friends:

“Reimagining Solidarity: Moving towards a culture of shared growth,” an article by A Growing Culture

Tree of Life, an eight-week online course organized by Advaya which explores the question: Could understanding our co-evolution with trees and forests be key to our human blueprint, and to our thriving amidst the biodiversity that exists? Register using our referral code “GREENDREAMER20” for 20% off single-purchase tickets to this course.

The latest from Green Dreamer:

“The political questions of science and technology,” ft. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

“Protecting space as ancestral global commons,” ft. Aparna Venkatesan

“The global sand trade and how it remade ʻmodernity,ʻ” ft. Vince Beiser

To continue your forest analogy, I'm glad you were able to give yourself a dormant period to rest and restore your energy so that you have capacity for new growth in the future. It takes an entire year between fresh peaches in our orchard and they are that much more precious because they are seasonal. So whatever timescale your creativity cycle takes, your thoughtful writing is fulfilling and well worth the wait.