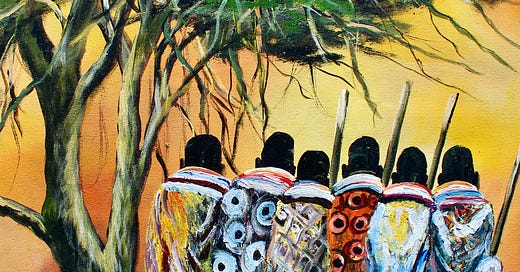

Honoring nomadic, pastoral land relations, ft. Joseph Oleshangay

How can "wildlife conservation" be problematic?

Legal systems have particular worldviews embedded within them that are not universal. They are the subjective logic encoded into the DNA of a nation state — layered on top of existing “laws of the land.”

This is perhaps one of the most important things I have learned in the last years — that legality is informed by political power, and that even our senses of morality are culturally molded.

So I had many questions when I interviewed Joseph Oleshangay, a Maasai human rights lawyer who has litigated high-profile lawsuits against their government — notably, regarding forced evictions of the Maasai community in Ngorongoro District for tourism and trophy hunting. The Maasai people have been resisting violent displacement from their ancestral territories carried out in the name of “wildlife conservation.”

I was curious about how Joseph navigates working within his nation state’s legal system, while trying to counter their conflicting values. And I point out to him:

“Sometimes, when something is all that [we] know, we forget the subjectivity of how everything works.

So you've had to learn the laws and logic and sense of morality of what is right or wrong — as imposed by your nation-state government's rule book. But they, and other foreign interests coming to your ancestral territories, didn't have to learn the language, laws, and ethics of your land and your community to engage with you.”

This is at the heart of the Maasai’s land struggles: How do they receive official legal recognition and rights to their nomadic, pastoral, and communalist ways of land stewardship — from a political system asking for proof of their private land acquisition and ownership?

The fact that commercialized forms of “wildlife conservation” involve large moneyed interests also distorts the incentives at play.

Joseph explains:

“We, as Maasai, as pastoralists, don't have the concept of private [land] ownership. So we say, ‘this is our land, not my land.’ Except for the house, which mostly belongs to the mother or the wife… then a big area for pasture for everything.

So you go to a court where the jurisprudence, the idea of law, is founded in a capitalist way. You must prove that this land belongs to you. This is the major problem.

We lose so many of the cases because, maybe we [have] 200 people going to court saying [we] are pursuing a case on behalf of the community — because we cannot bring 100,000 people to court.

And the court says, “This cannot be representative of the other…”

He says, “When did you acquire this land?” You try to say, “No, no, no, this is not how it works. We have been doing this for generations.” It's a concept that is not in law.

One of the bigger challenges is the jurisprudence point of view… We have, as a community, collective rights which are not written in law.”

But whose laws?

This is not to say that Maasai and other land-based communities around the globe have not achieved important wins through their nation states’ legal systems. I have more upcoming interviews on this as well.

But Joseph also acknowledges how much pressure there has been for the few members from his community who, like him, have received institutionalized education to be able to represent their community as lawyers.

“All the people put their trust in you like you are going to do justice for them. And you try to explain, ‘This is not a home for justice, literally.’ We litigate when there is no other option. […]

And if you are still on the land, going to court should be the last resort because it could be the channel for you to lose the land.

So it's complicated. But… you also try to play with the rules and ensure that your people get justice.”

Joseph and I also go on to explore how the Maasai’s ancestral lifeways blur the lines between life and “wild” life — showing their food, medicine, culture, spirituality, stories, and music as inextricably woven into the plains and highlands where they call home.

If this speaks to you, I welcome you to sink deeper into this discussion here.

(You can listen to this conversation here or via Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or any podcast app, and view our transcript and episode resources here.)

"Never listen to the empty words that there are places to relocate the Maasai, because you cannot carry the mountains.” – Joseph Oleshangay

Invitation into reflection:

What are some of the underlying worldviews and values of your nation-state government’s legal system that you are curious to unravel?

My podcast interviews and this newsletter rely on direct community support!

Please consider joining as a supporting Substack subscriber today (or making a one-time donation here) ~

Sending spores of appreciation to all that you are!

Thank you🙏❤️