This essay connects the dots between my personal experience of being subjected to emotional manipulation by a romantic interest and our broader, self-reinforcing systems that exemplify narcissism. (Content advisory: This piece explores the theme of narcissistic trauma from the micro to the macro and metaphorical levels.)

I recently put an end to a relationship with someone with traits of vulnerable narcissism who I realize had put me through emotional abuse for the past months. My gut knew something was off, but I was not able to consciously pinpoint what was going on at the time. Instead, I was strung along by the rollercoaster, only now coming out of the fog. I feel like I am finally able to look back and make sense of what I was incapable of seeing when I was so immersed in the matrix.

From being love-bombed, triangulated, devalued, stonewalled when asking for accountability for his lies, to being gaslit through his cycles of self-victimization, I felt like I was losing my sense of self. Although I had been offered apologies over and over again, which I initially mistook as emotional maturity, I later realized they were performative. One of the quotes that hit me as I learned to make sense of my experience was this: “Apology without change is manipulation.”

Thankfully, I am now on my path toward healing. But I cannot help but feel immense sadness knowing that this person likely developed his toxic relational tendencies in part from his unresolved childhood traumas. I am left pondering: How do I tenderly hold this nuance of all of the above? How do I hold him accountable for the hurt he inflicted upon me while being understanding of the nature-nurture roots of his narcissistic behaviors—including the systemic oppression his family faced that troubled his upbringing, contributing to the psychological wounds that prevent him from cultivating the ability to think much beyond his self-interests?

This is not the first person with narcissistic traits who I have encountered in my life, but he is the first one expressing the lesser-known “subtype” of covert narcissism whom I had started becoming close with. I grew up with relatives with signs of grandiose, overt narcissism, and I also feel like I have engaged with more people with these tendencies in the last few years alone than I was ever aware of prior. This has become a recurring theme in my life seemingly begging for my attention.

A modern epidemic of narcissism

Ever so curious to connect the micro to the macro, I started wondering about the relationship between narcissism—rooted in deep fears of insecurity—and our broader socio-cultural-economic trends. As it turns out, there has been a historic rise in narcissism and a decline in empathy. A report finds that college students who hit campus after 2000 “have empathy levels that are 40% lower than those who came before them.” Many social scientists also believe narcissism to be a modern epidemic.

What underlies these troubling findings? Researchers can only speculate. But Professor Peter Gray speaks to the increased pressure for individualistic achievements, coupled with the decline in time for social play, as a key factor.

“When achievement is defined as getting the best grades in school, getting into the best college, winning individual sporting competitions, and the like, then the focus of thought is on the self, and others are seen as obstacles, or as people you must defeat, or as people you must manipulate to serve your ends…

Closely related to the increased pressure to achieve is the decline in play. Over the past several decades, we have witnessed a continuous and, overall, dramatic decline in children’s freedom and opportunities to play with other children, undirected by adults… Correlational studies have revealed that children who engage in more social play with other children demonstrate more empathy, and more ability to understand the perspective of others, than do children who engage in less such play.”

In a similar vein, a study looking at the sociocultural factors influencing empathy points out that “Narcissism scores are higher in individualistic cultures compared with more collectivistic cultures.”

Part of their inquiry was whether modern capitalistic cultures are nurturing narcissism. They note:

“Teaching children individualistic virtues may contribute to lower self-esteem… Individualistic societies promote achievement-dependent self-esteem, i.e., a self-esteem that is threatened by constant social comparisons and the necessity to achieve more than other individuals…

Individuals who grew up in West Germany may have lower, achievement-dependent self-esteem. In contrast, collectivistic societies are directed toward maintaining social harmony. Individuals who grew up in East Germany may experience higher self-esteem, because it appears to be more independent from achievements and social comparisons.”

It is difficult to draw causal relationships when there are so many dynamic factors at play. Nevertheless, people’s sense of adequacy can be influenced by their situated cultural narratives of how one ought to calibrate their self-worth. A society prioritizing values of collaboration and relationships can result in their members understanding their roles and enoughness differently than a society prioritizing values of competition and individual gain.

People’s sense of self-esteem, then, should be seen as relative, contextual, and symptomatic of the deeper socio-cultural-economic circumstances that they are both part and product of.

Another analysis of America's narcissism epidemic stresses the socio-economic conditions further:

“There is another way to look at the rise in narcissism—as a defense mechanism. Narcissism is often driven by low self-esteem and insecurity. Since the 1950s, wealth inequality has risen, cost of living has exploded, especially for housing, and puchasing power has stagnated.

Combine these economic pressures with the competitive, pressure-filled media environment since the turn of the century and you have a recipe for a rise in narcissism. And sadly, narcissism is linked to elevated hostility and aggression towards others.”

Narcissistic traits necessitate context

It is important to note the limitations of labels when trying to understand the complex human experience. I generally shy away from using categories that noun-ify individuals and prefer using them as descriptions subject to change—honoring the ways that people express themselves differently across time and varied circumstances. One can find examples of this in the reality television series Squid Games: The Challenge, in which many contestants felt regrettable needs to make cut-throat decisions against their so-called allies due to being placed in a context where they knew only one person could come out “on top”—to win the prize money of $4.56 million. In such an extreme scenario, many people arguably became more narcissistic versions of themselves because the context incentivized it.

No matter, narcissism can be understood as both a trait along a spectrum and past some point, supposedly a “personality disorder” that can be shown through neurological differences—where the left anterior insula region of one’s brain which is responsible for emotional empathy has fewer cell bodies. This does not mean that people are “fixed,” as neuroplasticity, though it declines with age, demonstrates that one's brain can change, reorganize, or grow neural networks based on experience. But it does speak to the nature-nurture question—that some people have a greater predisposition for narcissism, that some people may be influenced by early childhood experiences to develop such tendencies, and that there are both possibilities and limitations to moving away from one’s baseline.

Still, I am wary of pathologizing narcissism even at its extreme—because that redirects the focus away from the possible culprits of larger socio-environmental changes that could impact collectives of bodies across generations. Ayesha Khan, Ph.D., stresses: “Our identity and behaviors are shaped by our relational and systemic experiences and our ancestral trauma, which actively alters our physiology and genetic code.” They conclude, “Narcissism is a harmful byproduct of capitalism and systemic oppression, but not a biological disorder.” This adds weight to the underlying message that people cannot be fully understood when isolated from their contexts because they are symptomatic of their circumstances and environments.

None of this is to say that there is a simple relationship between abusive conditions and narcissism. Early childhood or generational trauma can, of course, impact people differently—including but not limited to the development of maladaptive relational tendencies like co-dependency, narcissism, or numerous other possibilities. Also, no two persons experience, react to, or are affected by the same traumas or strains in the same ways. Knowing the vast complexities that these inquiries entail, I am mindful to maintain space for nuance and yes-and rather than drawing rigid conclusions.

Regardless, the point remains: If narcissism has its roots in feelings of insecurity, it becomes impossible to disentangle it from the broader contexts of what has been making more people feel insecure—because insecurity necessitates context.

This modern picture, for many, has looked like aggravating oppressive social conditions—including the need to survive within exploitative, extractive economies; the growth in “wealth” disparity making a majority feel less secure; systemic violence contributing to the breakdown of community; consumerism-driven media constantly telling people that they are not good enough; and cultural narratives of individualism tethering people’s self-worth to the illusion of their independent achievements.

When all of the above are true for an increasing number of people, we can only deduce that an increasing number of individuals are experiencing the byproduct wounds of some form of abuse or trauma. Whether or not people can even properly tend to these contextual injuries in individualistic ways—separate from one’s embedded daily life—is a different question worth exploring. (In alchemize: radical imagination for collective transformation, Gabes Torres leads a practice on “healing beyond institutions“ which helps to address this point.)

But what we can conservatively say, I believe, is that at least some of this growing collective trauma ends up being expressed as a rise in some people’s narcissistic tendencies.

So what, then, might be the impacts of the world having more and more people who have a hard time thinking beyond their self-absorbed concerns?

And what have been, and what will be, the continued impacts of our dominant socio-political structures modeling after narcissism and also rewarding narcissism?

Seeing narcissism as social allelopathy

There has been increasing evidence showing that “high-power” executives show greater levels of narcissism and that people with narcissistic traits are more likely to climb corporate ladders faster and take control of leaderless groups. As people examine the roster of the world’s most “powerful” political leaders, it is also not difficult to genuinely wonder why so many lack empathy in their decision-making.

Unfortunately, this becomes a vicious cycle, as psychologists looking at the impact of power on the brain have shown how gaining power leads to an increase in “hypocrisy, moral exceptionalism, egocentricity, and lack of empathy for others,” according to the British Psychological Society. In other words, those who act more selfishly are more likely to be able to accumulate power-over, and then being in those positions of domination further dulls their lack of regard for others.

If narcissistic traits in a person exhibit themselves as a lack of empathy and a constant need for “narcissistic supply” to validate their fragile self-esteem, then capitalistic socio-political systems can be seen as exemplars of narcissism.

The socially constructed measure of “economic growth” central to how many nation-states define their “well-being” fabricates their foundational sense of inadequacy.

That feeling of insatiable never-enoughness then drives the states’ needs to pursue an endless “narcissistic supply” no matter what impacts they externalize—like hurting and exploiting people, lands, and other “resources.” There is zero empathy reflected in this type of system that maintains an eagle's eye on “growth” at all costs.

Just like how one’s sense of self-esteem ought to be understood as contextual and conditioned by broader cultural narratives, we can also understand the “self-esteem” of a collective as being storied through social constructs in much the same way.

Extractive economies choose to define themselves as never having enough, so they must orient their entire existence toward taking, taking, and taking. Meanwhile, their politicians utilize such out-of-touch numbers showing “economic growth” to tell their citizens that life has never been better. In reality, more and more people find themselves feeling politically gaslit as their real struggles of insecurity go unseen and untended.

Performative apologies continue to be issued, state propaganda continues to manufacture consent, and representation politics continue to be deployed to appease and offer some optics of change—while little is substantively being done to reconfigure power relations and material realities.

I recall: “Apology without change is manipulation.”

If extractive systems are indeed breeding grounds for narcissism, and if, in turn, people with such tendencies are more likely to condone and perpetuate exploitative relations and policies, then this becomes a social mirror of the ecosystem allelopathy which I explored in my last article, “Beings as verbs”.

While allelopathy refers to how certain plants biochemically alter their environments to render them more or less hospitable to ally or competing species, my piece highlighted the allelopathic impacts of aggressively growing grasses introduced to overtake rainforest communities. The dominance of these grasses disrupts local water cycles, dries out the terrain, and makes the bioregion more prone to droughts and fire—in turn rendering it harsher to the pre-existing wet forest native species and more conducive to the spread of those dryland grasses.

A vicious cycle gets set into motion, as the monodirectional change that is reconfiguring the community continues to reinforce itself.

Here, I posit that the epidemic of narcissism is social allelopathy.

Narcissistic economics and politics are more “rewarding” for people expressing narcissistic behaviors, and people with such traits are also more likely to reinforce systems predicated on greed and dissociation from our interdependence. People who refuse to operate by these extractive logics are also less likely to accumulate the type of power-over that the “narcis-system” validates. This means that those positions of power-over that dominate the modern world are inevitably going to end up disproportionately consisting of individuals who have less capacity for care for our collective well-being.

Our broader trends toward the monopolization of power across industries, the increasing “wealth” disparity within most nation-states and internationally, and the increase in anxiety, depression, and chronic diseases that more accurately represent people’s quality of life are all reflective of this “narcis-systemic allelopathy.” And it really is more than social allelopathy, because it is not possible to separate the social from the ecological, cultural, and spiritual. The ramifications of narcissistic decision-making include devastating impacts on our more-than-human bodies and communities.

This vicious cycle is already in motion, as the monodirectional change that has been reconfiguring the laws and organization of society at large is continuing to reinforce itself.

“Underlying [Self-Devouring Society] is the premise that capitalism must continually grow, ceaselessly producing more, eliminating labor as it goes, until there is nothing left.

It is not merely self-devouring economically but will take down society as well. Because its residue is narcissists, like we have never seen them before. So far, Jappe is right on track, as narcissists are suddenly everywhere.” –David Wineberg reviewing Self-Devouring Society by Anselm Jappe.

But all is not lost. Awareness is the first step to exiting the fog. Thresholds and breaking points do exist. There is neuroplasticity in our collective consciousness. And we can unwire and rewire the present exploitative logic underpinning a deeply troubled society.

Upon reflection, I think part of the reason I condoned being emotionally manipulated—at least until I reached my breaking point—is that I am a deep empath at heart. I wanted to practice empathy for someone who was a victim of childhood neglect even though he weaponized his unresolved trauma against me. Similarly, I wish to practice empathy to see the perpetrators of harm across the globe, especially victims of abuse who later become aggressors, as scarred and disoriented and in need of guidance and healing. Once again, this calls on me to maintain a container of tenderness to hold all of the above—centering the healing of those subjected to violence or abuse in any form, not letting the aggressors in any given situation off the hook, while also still attempting to recognize their deeper, unmended wounds.

At some point, though, this cycle of “hurt people hurt people” needs to no longer be an excuse or a point of deflection or explanation, but simply be put to rest.

So I feel a need to hold this sensitive spaciousness simultaneously as I co-conspire against the allelopathy of narcissism. After all, without disrupting the toxic societal trends that are co-opting power towards the abuse of power, we might just find ourselves asking over and over again why history continues to repeat itself.

(To be continued—via a part 2 on waking up in the twilight zone of empire.)

Other updates:

Read my last essay, “Beings as verbs: The messy reconfigurations of life that are remaking the world”

Tap into my latest podcast interview on “Lessons from lichen worlds” ft. Laurie Palmer of The Lichen Musem

alchemize: radical imagination for collective transformation, Green Dreamer’s new 8-week program of daily imagination practices and creative prompts is open for enrollment! Sign up with “EARLYBIRD15” for $15 off until 12/20.

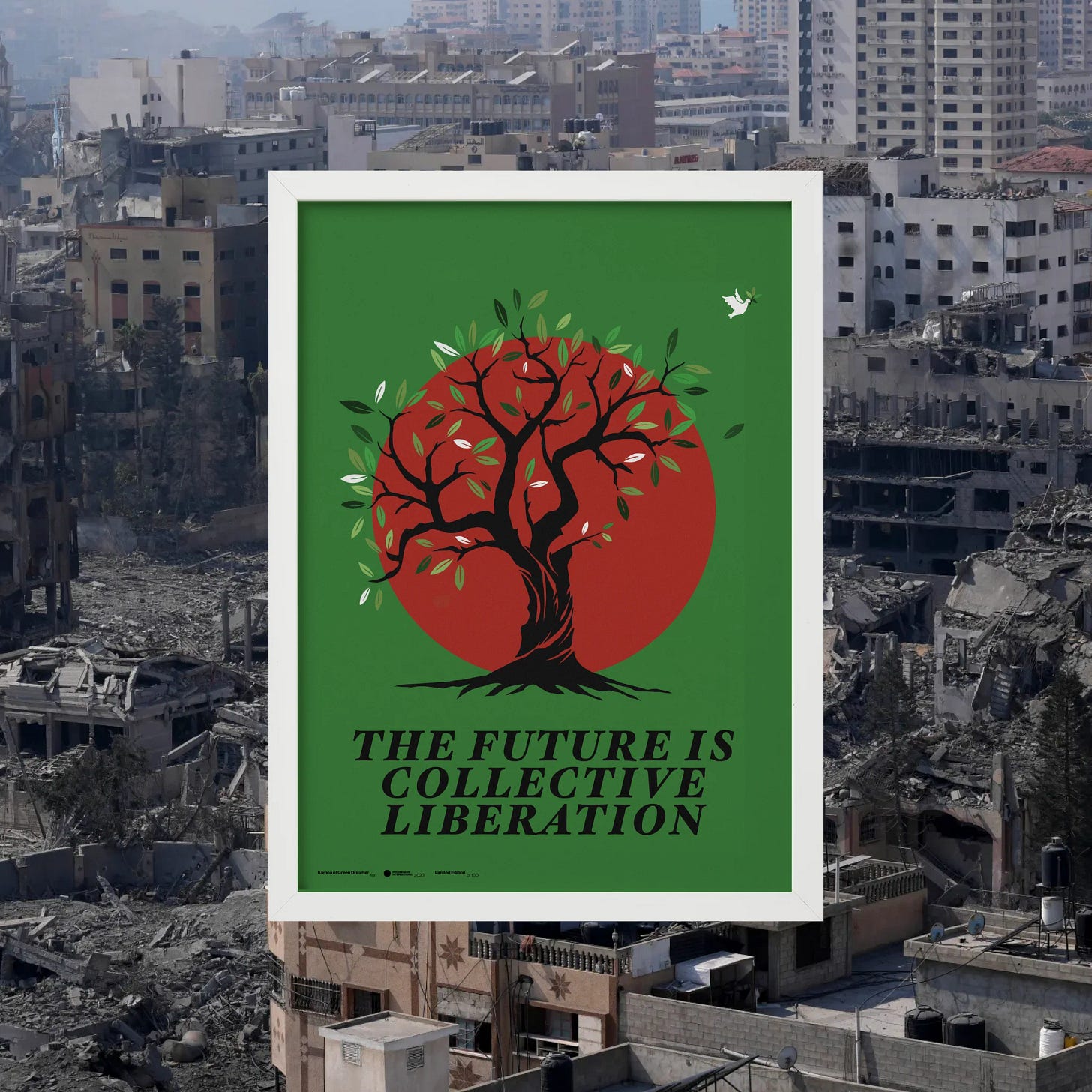

I created this artwork, “THE FUTURE IS COLLECTIVE LIBERATION,” for Progressive International's collection of political posters for sale. Check it out.