Bioregional, Indigenous fibers list: Re-rooting fashion systems in place

Moving away from seeking "the most sustainable XYZ" to learning "the best fit" for this biocultural region

Organic cotton, linen, hemp… these are what we'd commonly hear as “the most eco-friendly fibers” in fashion.

But imagine if everyone bought and wore clothing made with these commonly named fibers, driving up the demand. What would happen?

In order to keep up with the scaled production of clothing made with these plants, ecosystems teeming with their own bioregional diversity would have to be converted into organic cotton, flax, and hemp farms—many of which may be monocultures. They would inevitably be grown in places where they're not locoregionally suited, meaning they could potentially become invasive species or require more added inputs of labor and resources to upkeep.

This reiterates a message you may already have heard me share: Sustainability needs to be contextualized!

“Organic”, “low-impact”, and “biodegradable” are insufficient to qualify something as “sustainable” because they overlook the much-needed contextualization of place—including its locoregional ecology, culture, and history.

While ecological impact assessments often seek to find fibers with the least water use, energy use, and land use, the danger lies in their underlying assumption of such a thing as “best”—when it's more so about “bioregional fit”.

As such, the presumption of there being a one-size-fits-all answer can lead to ‘solutions’ that actually further species homogenization and the degradation of biocultural diversity.

Rather than turning to these top-down analyses to determine the answers to “the most sustainable _______”, it's crucial that we learn the biocultural history of where we are, support Indigenous-led land protection and revitalization efforts, and cultivate reciprocity with the ecoregional landscapes we each call home.

There is a lot of work that needs to be done to re-root our fashion system to place. The challenges include having to work with our current globalized, complex supply chains, a trend towards monopolization and the centralization of power in the industry, and the loss of biodiversity in the name of scale and ‘efficiency’ (valued over other vital metrics of life like biodiversity and ecological function).

But in order to address widespread ecosystem breakdown and the climate crisis, we have to shift towards fashion systems that regionalize production, decentralize power in the industry, and diversify the materials we use.

All of these elements must go hand-in-hand: regionalization, decentralization, and diversification. But our awareness, unlearning, and relearning must come first.

So I've compiled this list of the numerous land-based fibers Indigenous or that have been significant to communities across different continents.

The point isn't that we should work towards localized systems that only ever utilize native plants—as so many species have already been transported all over the globe already (some additive; others ‘invasive’). This makes a black-or-white, ‘purist’ approach difficult and impractical. But in attempts to relearn which species are bioregionally suited to and life-enhancing for a certain landscape, looking to Indigenous or culturally significant species evolved to thrive in those regions is always a good way to start. (Though note that the work of supporting Native communities and respecting Indigenous sovereignty must always happen in tandem.)

I'll continually add to this list as I learn more, but my hope is that it can act as a starting place for us to enrich our biocultural literacy and better understand what truly regenerative, place-based, and diversified textile and material systems may look like.

North America:

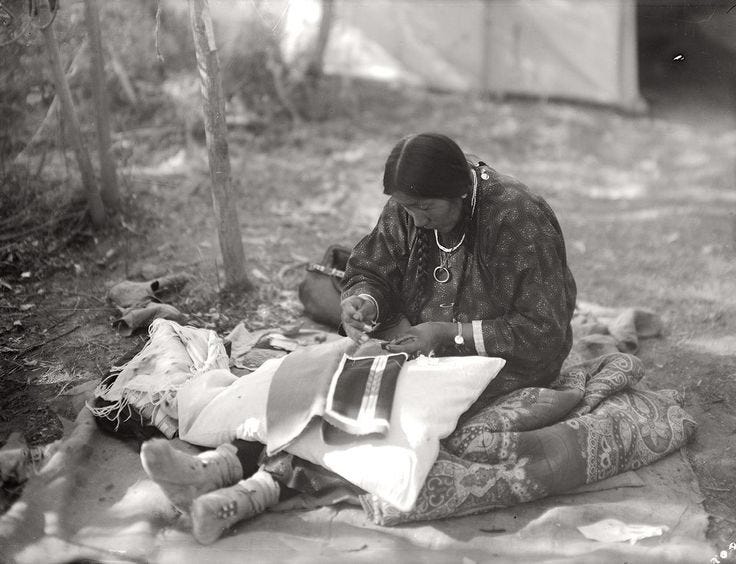

Animal hide: used significantly in the Great Plains, where the native ecosystem does not have many plant fibers to work with. Clothing made with animal skin was warm and durable, making them suitable to the ecoregional climate. Hides were often sewn together with animal sinew and porcupine needles.

Arizona wild cotton (Gossypium thurberi): native to the Arizona desert; used by Native Americans in the desert Southwest as food and fiber for thousands of years.

Beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax): common in the Olympic, Cascade, northern Sierra Nevada, and the Rocky Mountains. The smaller leaves were used as material for clothing, such as dresses and hats, and the larger leaves were used for basket weaving. The rhizomes were even roasted as food, and the roots boiled as hair tonic or medicine for sprains.

Cedar tree bark*: used by communities primarily in the Northwest regions. Made into clothes, raingear, mats, ropes, blankets, tinder, sewing thread, and wicks.

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca): native to Southern Canada, Saskatchewan to New Brunswick; south to Georgia; west through Tennessee to Kansas and Iowa. Used by Native Americans as fibers; later used as natural fill for floatation devices and life vests, pillows and comforters, etc.

Human hair: used as symbolic decoration by certain tribes on clothing.

Mulberry bark fibers*: used by communities primarily in the Southeast Nations

Redwood bark*: used by communities primarily on the West coast

Sagebrush bark*: used by communities primarily in The Plains

Swamp Milkweed (A. incarnata L.): native to Manitoba, Quebec, and Nova Scotia; from New England south to Georgia; west to Louisiana, and Texas; north to North Dakota.

Wool: first from the region's animals such as bison, then later with wool from sheep introduced by European colonial settlers.

Yucca: often used for sandals, ropes, mats, clothing, nets, hairbrushes, mattresses, and baskets; the leave points often were used as sewing needles. Soapweed (Yucca glauca) was a significant medicinal and fiber source.

*Across all continents, people traditionally used fibers extracted from tree bark to make textiles, tools, and other household items—including clothing. While it may not be practical to make clothes from tree bark in the same handcrafted and mechanical way (as opposed to the chemically intensive processes used today to turn wood pulp into soft fabric), as they often ended up as textiles that feel scratchy and rough, there are other uses they could potentially still substitute, such as mats, rugs, cord, ropes, outdoor furniture, etc.

Central & South Americas

Animal fibers: wool from native camelids and grazing animals has been of great significance to local communities in South America. To this day, wool specifically from alpaca, llama, vicuña, guanaco (wanaku), mohair, and cashmere from goats to Argentina ‘are produced almost exclusively by smallholders in low input systems where they are critical for the subsistence of its producers by contributing raw material for homemade clothing, handcrafts for local markets or fiber for the textile industry. Most fiber production systems are located in marginal areas with goats and camelids grazing natural rangelands.’

Majagua: native to Porto Rico, Cuba, Mexico, Central America, and South America; bast fiber often used for ropes.

Henéquen: native to southern Mexico and Guatemala; used for rope and twine, and also for a traditional Mexican alcoholic drink.

Istle / ixtle: a general term describing stiff plant fiber obtained from various Mexican plants in the Agave and Yucca family; used for rope, twine, bagging, and as a substitute for animal fiber for brushes, cords, and lariats.

Maguey (agave): native to Mexico and Central America; used for food and drink, and also for making cordage net bags; commonly used by Mayan men.

Sisal (part of the agave family): native to Mexico & Central America; used for rope and twine, and also to make paper, cloth, footwear, hats, bags, carpets, textiles, etc.

Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum): native to Mexico and Central America; today, this variety makes up 90% of commercial cotton production.

Extra-long staple cotton (Gossypium barbadense): native to tropical South America; today, this variety makes up 8% of the world's commercial cotton production.

Mauritius hemp: native to Central America; used for bagging and other coarse textiles.

Kapok (Ceiba pentandra): native to Central & Northern South America; used as fill fiber, often for traditional floatation devices or bedding fill.

Pita Floja: native in regions from Southern Mexico to Ecuador; of significance to the Philippines. Used for fish lines and nets; also used to sew animal hides.

Caroá (Neoglaziovia variegata): from northeastern Brazil; flexible fiber three-times as strong as jute; used as twine, rope, nets.

Pochotes (Ceiba aesculifolia subsp. parvifolia): native to Mexico; a cotton-like fiber produced by the fruit of Pochote with antimicrobial properties; used as a part of traditional medicine to alleviate bacterial and virus infections; seeds often directly consumed.

Silk floss tree (Ceiba speciosa): native to South America; AKA Palo Borracho; the silky cotton in the capsules has been used as stuffing and filler; the barks have been made into ropes; edible or industrial-use vegetable oil can be extracted.

Samohu: designates a score of kapok-like, flossy fibers from trees of Ceiba and Chorisia; originated from South America; used like kapok as fluff, filling, floss, etc.

Tropical milkweed (A. curassavica): native to the tropical Americas (and has been found to potentially negatively impact migration patterns of monarch butterflies when grown outside of its native region); its milky sap can be poisonous and cause eye injury; can yield fibers and stuffing materials.

Aboriginal Australian carving; photo by Lindsay Black via Australian National Herbarium.

Australia

Animal skin and fibers: Australia's Indigenous peoples have long used leather and fibers from animals native to the continent.

Barks from a variety of tree species, such as the native hibiscus.

Black Kurrajong Tree (Brachychiton populneus): young roots and seeds consumed as food; its bark was used for nets, headbands, and fishing lines.

Blue Flax Lily (Dianella spp): used as an ingredient and source of food; its fruits can be eaten raw; its leaves are used as textile fibers; its roots can be boiled and drunk as a medicinal, immunity-supporting tea.

Geebung (Persoonia spp.): an important source of food for Aboriginal Australians; the bark was often turned into fishing nets.

Green Wattle (Acacia mearnsii): its gum is used as adhesive; the bark is used as string.

Kangaroo Grass (Themeda triandra): its seeds traditionally were ground and baked; strong fibers can be extracted from the leaves for making fishing nets.

Mat rush (Lomandra longifolia): the long leaves were used by Aboriginal Australians for weaving baskets or making bands for aching limbs, while the grounded seeds were used to make traditional soda bread (damper).

Native Flax, Wild Flax (Linum marginale): the seeds can be eaten; the stem iss soaked and beaten, turned into string as a bast fiber.

New Zealand hemp, aka harakeke (Phormium tenax): perennial plant native to New Zealand and Norfolk Island; many uses by Indigenous Māori society; leaves used to create a fiber, muka, for making durable, soft fabric for clothing. With this said, the exploitation of the plant, clearing endemic landscapes to make flax plantations, has threatened other native species.

Rice Flower (Pimelea linifolia): its fibers were used to make strings for nets.

Europe:

Animal hides and fibers: like all other continents, animal hides and fibers were often used in textiles and clothing as whole animals were used after hunting for food; for the Indigenous Sami people, gátki traditionally was made ‘from reindeer leather and sinews, but is now more commonly made from wool, cotton, or silk.’

Narrowleaf flax (Linum bienne): considered the ‘probable wild forebear of the cultivated flax’.

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica): native to Europe, and potentially also western Northern Africa and temperate Asia; bast fibers can be extracted from nettle to make linen-like textiles; has been used to make clothing in Europe for over 3,000 years.

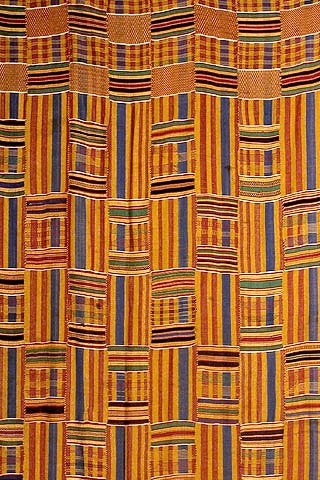

Pictured: Traditional Kente Cloth, the national cloth of Ghana.

Africa:

Animal hides and wool: Since the earliest of times, animal hides and fibers from native wild and domesticated animals have been used to make clothing. With the influence of western ‘modernization’ and cultural homogenization, many today buy store-bought clothing. But animal skins continue to be worn by more senior members of rural communities and tribes who continue to practice their traditional, place-based lifeways and cultures.

Barks from a variety of tree species, like the fig tree.

Bowstring hemp (Sansevieria): native to Africa & Asia; waterproof fibers used for bowstrings, cordage, ropes, mats, and nets.

Levant cotton (Gossypium herbaceum): native to southern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula; this variety makes up less than 2% of global production.

Malagasy silk (Borocera cajani): wild silkworms native to Madagascar; used traditionally to weave sacred burial cloth; more recently, local weavers have started to make wild silk scarves for tourists and the country's elites, and with local ecosystems increasingly vulnerable to fires and other threats, the silk businesses have supported local communities to better protect their forests in which the Malagasy silkworms call home.

Okra fiber: originated potentially from Ethiopia & West Africa, or from South Asia ; edible as the okra plant but also can be used as a bast fiber.

Raffia palm (raphia): a genus of 20 palms native to tropical Africa; R. taedigera is the species often used for raffia fiber; has been and still is made into ‘twine, rope, baskets, placemats, hats, shoes, and textiles’.

Asia & The Pacific:

Abacá (Musa textilis) aka Manila Hemp: a non-fruiting banana species native to the Philippines; its fibers are used to make of hats, hammocks, matting, cordage, ropes, coarse twines, and canvas; “Philippine indigenous tribes still weave abacá-based textiles like t'nalak, made by the Tiboli tribe of South Cotabato, and dagmay, made by the Bagobo people”.

Animal leather and fibers from species native to and abundant within the region

China Grass Cloth aka white ramie (B. nivea): endemic to East Asia; labor-intensive bast fiber used for durable fabric, fishing nets, and filter cloths.

Coconut Coir (Cocos nucifera): native to Southeast Asia & the Pacific Islands; fiber from coconut husks; used to make doormats, brushes, mattresses, upholstery padding, sacking, brushes, string, rope, and fishing nets.

Bowstring hemp (Sansevieria): native to Africa & Asia; waterproof fibers used for bowstrings, cordage, ropes, mats, and nets.

Hemp fibers (Cannabis sativa): originated from Central & Western Asia; one of the first plants to be spun into usable fiber 50,000 years ago; its fibers can be made into paper, textiles, clothing, insulation, etc.

Indian kapok (from the Simal Cotton Tree, Bombax malabarica): native to China and southeast Asia including northern Australia; produces cotton-like fibers often used for stuffing.

Indian lotus or sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera): native to a wide range of ecoregions across Asia and also the Caspian Sea; “A unique fabric from the lotus plant fibers is produced only at Inle lake, Myanmar and in Siem Reap, Cambodia. This thread is used for weaving special robes for Buddha images called kya thingahn (lotus robe)”; woven today using ancestral techniques.

Velvetleaf Indian Mallow (Abutilon theophrasti Medik): native to China; its jute-like fibers are used to make string, rope, rugs, and paper; the leaves are edible.

Jute (of the genus Corchorus): Tossa jute is native to South Asia; one of the most affordable fibers, second to cotton in the amount produced and variety of uses; bast fiber.

Rattan (general name for hundreds of climbing palms of Calamoideae): used to make rattan furniture and woven baskets; also traditionally used by Wemale women to make girdles around their waist.

Rhea (green ramie): believed to originate from the Malay peninsula; similar to the China Grass Cloth or white ramie.

Roselle / Rama (Hibiscus sabdariffa): native to Southeast Asia / West & East Africa; produces a bast fiber through water-retting processes;

Sunn Hemp (Crotalaria juncea L. ): native to southern India and one of their earliest named fiber plants; supports soil health as a cover crop; its soft fibers can be used as pulp to make non-wood paper.

Tree cotton (Gossypium arboreum): native to India and Pakistan; today, this variety makes up less than 2% of cotton production globally.

Additional food for thought:

Industrial imperialism and our extractive economic systems today, thriving off of homogenization, monopolization, and mass production to lower costs and maximize ‘efficiency’, seems to be directly at odds with diversification, decentralization, and localization.

For many Indigenous communities, whole-animal or whole-plant use seemed like a common practice—and respectful and resourceful. For example, for some plant, the roots were often used for one thing; the stems and leaves for something else; the seeds for something else; the fruits for something else… etc.

While ‘going back’ to undo the introduction of nonnative species to all parts of the globe isn't practical (and sometimes such introductions were actually beneficial), at a time when the powerful forces of economic globalization are clearly pushing us towards ecological homogeneity, paying special care to protect and steward a wide variety of endemic species can be a meaningful way to support our ecosystems to enhance their resilience against degradation.

Due to the intricacies and complexities of place-based knowledge, multinational corporations that currently dominate the material industries are not suited to lead their respective fields into the future of sustainability—no matter how much money they invest in ‘research and development’ to innovate solutions. I'm convinced that sustainability requires both ecosystem restoration and re-indigenization (or decolonization). And people who hold such landscape-specific, biocultural knowledge are best equipped to lead us in that direction.

Again, this list is a work-in-progress that I will keep adding to and refining. Happy browsing and learning :)

x kaméa

Thank you for supporting my reader-powered newsletter by becoming a paid subscriber or making a one–time donation here :)

I love this, well said. I'm in Aotearoa and looking to replant / restore native plants in the garden. I had thought about how some have multiple uses, historically, but hadn't really thought about uses beyond medicinal or culinary; fabric is next level but would be really interesting to learn about even if I'm not making it myself. I started researching native flora in my suburb and it turns out it varies from plants in the higher elevations in neighbouring suburbs but there are a few that have been used nationwide for centuries....